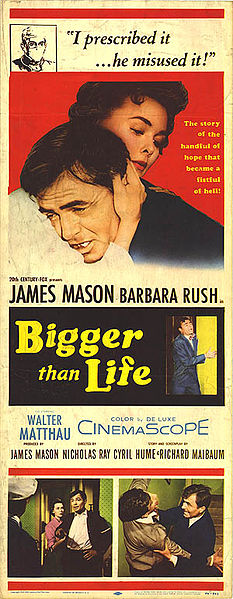

In the 1950s the habits and fashions of suburbia came to acquire a hitherto unprecedented prestige in American eyes, becoming a place of envy, desire, ambition and strongly apolitical normality. Movies helped with this idea, combined with advertising and a boom in technological consumerism — a final remider of — and an apology for the inadequcies of the American Dream. Bigger Than Life (1956) from director Nicholas Ray and starring James Mason and Barbara Rush was one of the first stabs at portraying the nightmares latent in this aspirational lifestyle, and has as its subject drug abuse — not in the sense that a movie like Reefer Madness does — but with an abuser who is as representitive of the patriarchy as could be found.

Certainly, Bigger Than Life is one of James Mason's finest moments.

If I read the quote correctly, Jean-Luc Godard numbered Bigger Than Life among the top ten best films ever made — in his opinion. These are not the random thoughts of an egotistical auteur, but a decent reaction to a powerful, terrfiying and subversive film which was in its day rejected at the box office, but which is quite stunning when veiwed today. It doesn’t sound like it could stretch to much — a schoolteacher becomes addicted to new wonder drug cortisone — but in the way that the drama builds, and in the damage we see the addict creating, Bigger Than Life succeeds its expectations and borders on the shocking at times.

James Mason rocks suburbia in Nicholas Ray's Bigger Than Life (1956)

For those used to the unrealistic drama of police procedural or the camp (or code) psychology of film noir ... or even the cinematic spectacle of the epics ... seeing two or three actors creating such a great amount of tension is unusual. Most of the effects of Bigger Than Life emerge in scenes between James Mason — who plays cortisone addicted teacher Ed Avery — Barbara Rush, playing his wife — and Christopher Olsen who plays his son.

James Mason and Christopher Olsen in Bigger Than Life (1956)

The art of Hollywood concerns surface clues. The great example of these in Bigger Than Life are the posters that James Mason has up over his house — foreign destinations, pretty much all European — a dream on every wall of his family home — and all places he has not been. The posters are great suburban decoration, indicative of the middle class at their softest, most ridiculous. Part of the household action of Bigger Than Life takes place at the hearth, under a map of the earth, suggestive of much of the same — an image with an Enlightenend edge, and ironic because the world is a place that could not be further from suburbia.

Barbara Rush (Bigger Than Life, 1956)

The focus is so strictly on the ensmble of the husband, wife and child and their acting together, that when James Mason’s cortisone induced breakdown starts off, Bigger Than Life becomes frightening. It’s the power of the father figure, and the vulnerability of his child that makes it so good — and you often find yourself waiting and watching for James Mason to snap. Usually he doesn’t, somehow releasing the tension in another way — drifting off maybe — or having a Nietzschean or Biblical moment.

Barbara Rush as the wifelet does what she can and attempts to talk James Mason out of his mania and notices early that things are going wrong. The way Barbara Rush, James Mason and Christopher Olsen who plays their son Ritchie, work together things become truly frightening. For spotters, you will notice that Christopher Olsen also played the kidnapped child in The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Mason’s charcater is a teacher, and possibly the highlight of the film is when he launches a right winged tirade at a school parents night. Right wing is not fair in describing what James Mason’s cortisone-addicted teacher’s rant is like — but the drug addicition brings out a Niteszchean Will to Power in the man — a sudden clarity concerning social institutions and the base normality of people’s emotions and desires.

In fact, in these moments of what seem to him like extreme clarity, James Mason as 'Ed Avery' sees both state and church as letting down society, but instead of doing anything about it other than grousing — something suburbia is shown to excel at earlier in the film — he comes up with a madder and more Abrahamic solution.

Bigger Than Life peaks in several places, and reveals more psychology than the poster or any trailer could ever convey. Nicholas Ray, James Mason and Clifford Odets (who scripted some of the film) were all in their ways extreme creatives for whom the system was difficult to negotiate, and Mason’s character is tormented that he might be ‘bigger than life’ — bigger than suburbia, greater than the system, and basically wasted by the rigorous mores of middle class living. Ed Avery then, like many artists, has these Nietzschean moments when everything seems so clear, so easy and very much below them.

Family breakdown in the mid 1950s, in Bigger Than Life (1956)

For James Mason fans it is a must see — and for Mason himself it was a ‘must-make’ as he produced it himself. Nicholas Ray made some of the best pictures of the era, including Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and the much loved noir In a Lonely Place (1950). It didn’t end too happily for Ray — a familiar Hollywood story — but much of that was down to his own inability to resolve the demands of the business with his own artistic desires and cravings. It’s a common story — only the popcorn salespeople really make it in Tisnsel Town, and like suburbia, it’s no place to try any serious boat-rocking.

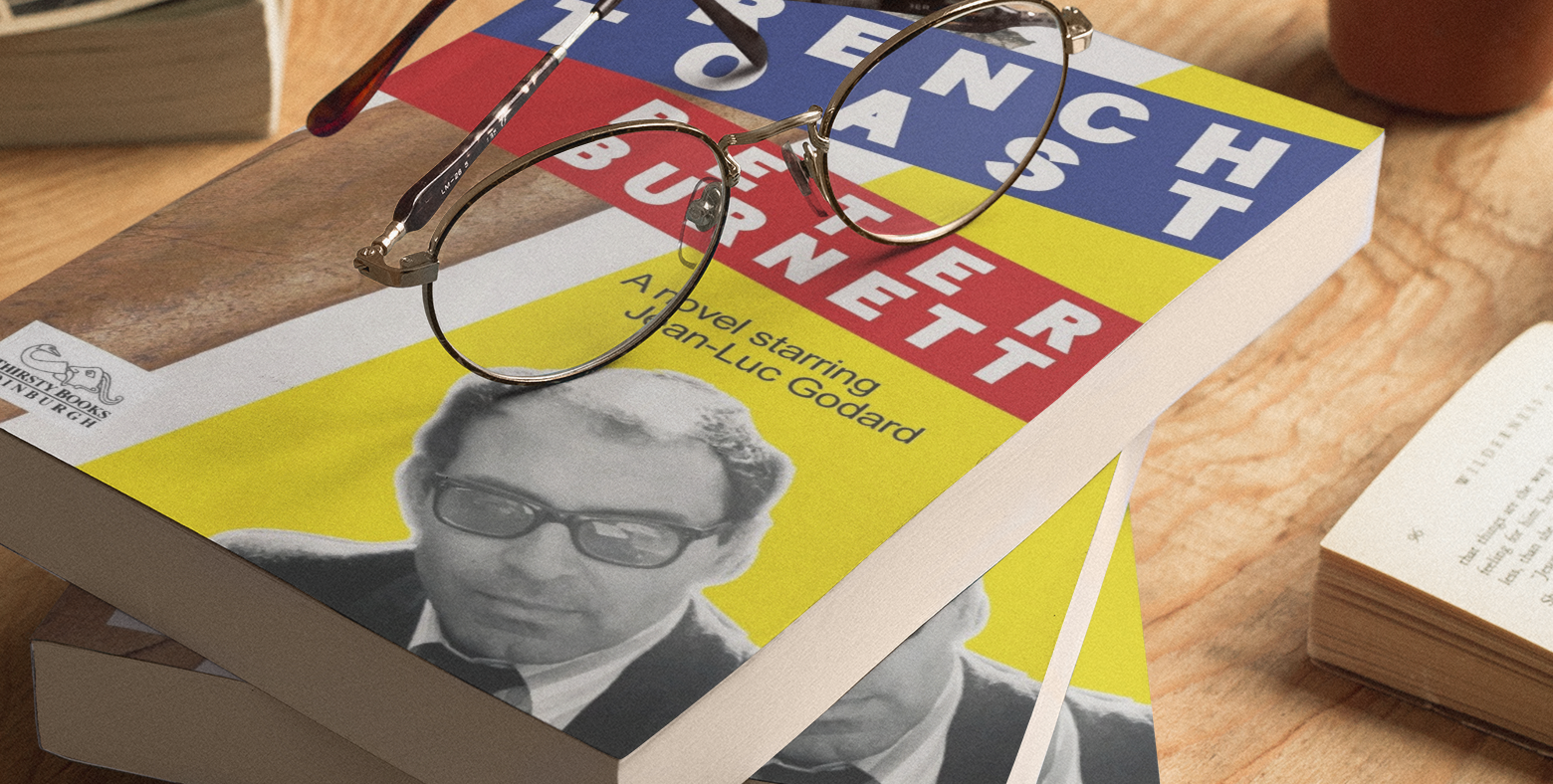

Image Path for Bigger Than Life theatrical poster

Bigger Than Life at Wikipedia

Walter Matthau in Bigger Than Life (1956), his third major film role

Gosh! My bad. But I can't believe I got to the end of this article without mentioning Walter Matthau, who plays Ed Avery's best friend, the gym teacher. It's a pretty straight role for Matthau, and Bigger Than Life was his third film role actually, and he hadn't yet established that niche which he succesfully carved out for so long, and which gave us The Fortune Cookie, Earthquake! and California Suite among so many others.